An event in the continuing saga of BT2

By Garland Davis

BT2 and the widowed Navy Wife (not WestPac widowed) who he was currently rolling around with were off tp the Air Force Commissary. Here he was acting like a fucking brown-bagger. She was a nice girl. He was hoping the ship left for WestPac before she sprang the trap.

BT2 didn’t feel so well this morning. His gut was roiling. She spent a good part of yesterday afternoon and evening teaching cake baking and decorating to a group of neighbor women and one MilkToast Pussy-Whipped husband.

BT2 called up that fucking Stewburner (Me) and invited him for a few Coldies. Stew showed up with that skinny-assed MM. The one who dived through the window of a moving 90 Yen taxi outside the Yokosuka Main Gate.

They had a case of cold beer, a fifth of Jack, a ten-pack of Taco Bell tacos, and a half dozen bean burritos. It would be a miracle if his gut wasn’t fucked up this morning.

When they arrived at the Commissary, his girl said she wanted to run into the BX for a minute and would meet him at the Commissary.

As our valiant BT entered the store his Shit-Light came on, blinking furiously. He spied the Restrooms and as he stared to move toward then he shit all over himself. He scurried into a toiled stall, wiped his ss and cleaned himself up as best he could.

Just outside the toilets was a tank of what BT2 called Cripple Karts. He figured shitty pants should qualify him. He fired up the cart and started shopping, probably leaving the odor of shitty drawers wherever he went.

He was ready to checkout when his girlfriend caught up with him. As hey were putting their purchases on the counter, she wrinkled he nose and said, “Something smells like dirty diapers!”

BT2 said, “Let’s get the hell out of here, I shit my pants.”

Her, “My God!”

As they departed the store, the PA system announced, “Clean-up crew to the Men’s Restroom, immediately!”

His ex-girlfriend (he figured),shaking her head, removed at towel from the trunk and spread it over the passenger seat.

They left the base and started home. As they entered the freeway (I’l bet you guessed it), he shit himself again. The liquid shits took the path of least resistance, up his ass crack and half way uphis back with a great gurgling sound.

There was a hint of Taco Bell in the air!

The Ex (He was sure of it now) said, “Go into the back yard and take off those pants.”

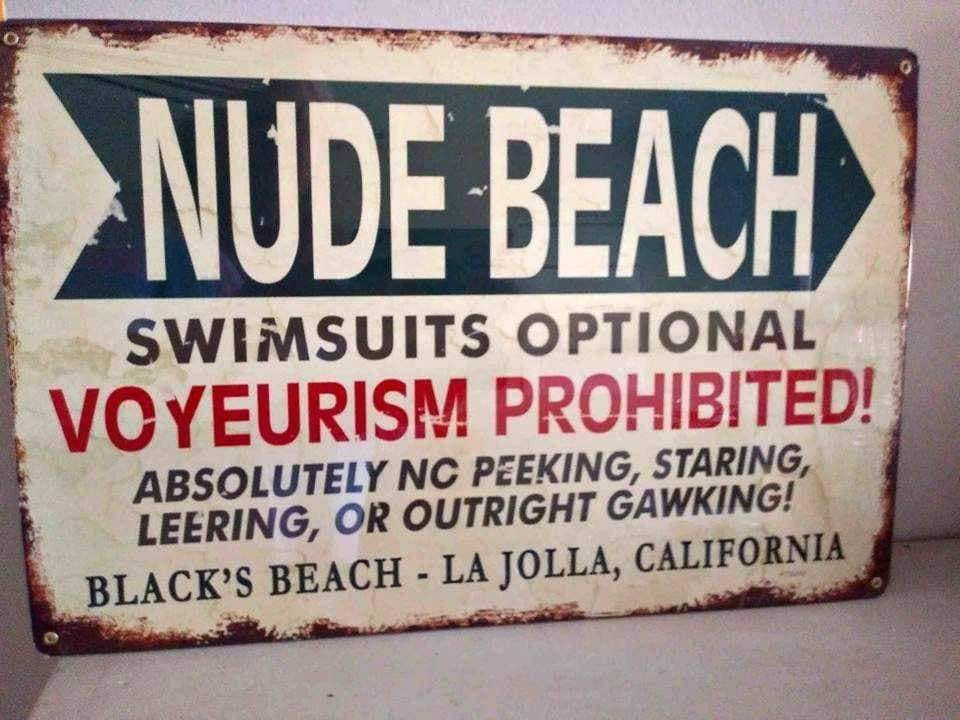

He thought, If anyone is looking out the windows of the two story houses surrounding the yard will see him with nothing on but a t-shirt, dancing around while she hosed him off with the icy water of the garden hose.

She said, “Don’t you dare use my bathroom. Use the shower upstairs.

As he climber the stairs, wearing only a t-shirt that was shot stained half was up the back He was dreading pulling it over his head when he shit all over the stairs…